All of a sudden it’s LMS week* in mostly-US higher education. Nudged by the imminent Educause annual conference, there’s a whole pop-up festival of reflection on why we still have enterprise learning management systems—and why we have the ones we have.

Audrey Watters, D’Arcy Norman, Phil Hill, Michael Feldstein, Jared Stein and Jonathan Rees have all contributed to this thoughtful and detailed conversation; anyone who thinks universities just woke up one day trapped inside a giant LMS dome really should read each of these at least. And Mike Caulfield has nailed one of the key problems: LMS features that don’t deliver the function associated with the name—in this case, the wiki tools in an LMS that rhymes with Borg.

As Audrey Watters rightly points out in her look over the wall at what lies beyond the LMS, the natural mode of LMS development is incremental, calibrated to the traditional operations of education institutions. The bottom line is this: content goes in, grades come out, and the whole thing can be flushed and repopulated with new learners the next time it runs. The LMS is particularly efficient at delivering sequential learning, and so it’s learner-centred in the same way that IKEA is customer-centred.

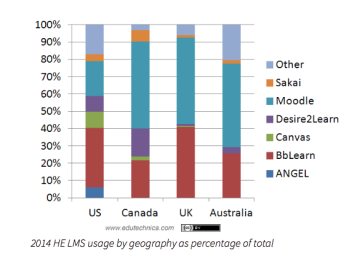

But the LMS story isn’t centrally about user experience. It’s a story about corporations, their investors, and their attention to higher education as a market. This week, George Kroner and his colleagues at the Edutechnica blog revisited their 2013 analysis of four countries in the global LMS marketplace, to see how the market share of key players has shifted over the past 12 months.

This is the state of things as a bar chart:

It’s a flattening visualisation that distorts the dollar value of the Australian market to an extraordinary degree, and it’s triggered a rerun of last year’s polite shoving between George Kroner and Allan Christie, General Manager of Blackboard’s ANZ operations, as to what counts as the Australian higher education market.

Put simply, it is generally accepted that there are 39 universities (38 public, 1 private) in Australia. (Allan Christie)

In short, I do not consider the list of the 39 universities to be a complete representation of higher education in Australia. (George Kroner)

The thing is, the entire Australian market is a hill of beans in comparison to the US. This is why we don’t belong on this misleading chart, but it’s also why our LMS market behaves the way it does, and so strongly favours the existing near-duopoly. In all but three of our generally agreed major institutions, one well known LMS has the advantage of incumbency, and the other well known LMS has the advantage of not being the incumbent, which is unpopular with its users in the same way that politicians are: generically. In a small system where everyone knows everyone, the influence of other institutions’ decisions is direct and intense. It tethers aspiration to conformism, and cautions against risk. Look at the neighbours, we say, they bought a Kia. Or the other one. Either way.

But this year, the disputed inclusion of Australia’s non-university providers is newly significant. The constitution of higher education in Australia is the subject of a substantial reform bill currently under Senate investigation (submissions to the Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment have just closed, and you can check them out here.) If the Higher Education and Research Reform Amendment Bill passes, it will change the relationship between the generally agreed 39, and the less well understood mix of others who can award degrees but until now have been excluded from Commonwealth funding.

No one’s sure exactly how Australia’s universities will adapt to all this, or how the non-university providers will be able to take advantage of their access to funding previously reserved for university places. But it’s likely that over the next few years LMS selection in the whole higher education sector will be sensitised to the attraction and retention of students who have grown up online, who are facing higher levels of education debt, and who will be vigorously encouraged by price signalling into comparison shopping. They will encounter a university system with more feedback mechanisms, more features, more special offers, and more personalised interventions of all kinds. Even if we’re not yet at the stage of installing lazy rivers, our online environments will become potentially distinctive campus amenities just like our libraries. Their quality, efficiency, and accessibility will become important in new ways, both to students looking to move quickly through degrees and sub-degree programs, and to university leaders looking for ways to expand and secure new markets, while keeping the overheads from teaching as low as possible.

Meanwhile many senior executive decision-makers setting the strategic direction for the use of these systems will still come from the generation whose own undergraduate experience (and perhaps whose academic careers) avoided online learning altogether. This is one reason, I think, why they have a view of LMS use that is far more utopian than most academics or students. It’s also the reason that universities underestimate by a very long way the proportion of academic staff workload that should now be reserved for LMS resource development, not just in exceptional circumstances like LMS change implementation, but all the time.

The result of this failure over many years to recognise the time needed to use an LMS well means that we end up with the situation Audrey Watters describes:

The learning management system has shaped a generation’s view of education technology, and I’d contend, shaped it for the worst. It has shaped what many people think ed-tech looks like, how it works, whose needs it suits, what it can do, and why it would do so. The learning management system reflects the technological desires of administrators — it’s right there in the phrase. “Management.” It does not reflect the needs of teachers and learners.

This is right, but it’s not the consequence of essentially bad design. The LMS is specifically good at what universities need it to do. Universities have learning management systems for the same reason they have student information systems: because their core institutional business isn’t learning itself, but the governance of the processes that assure that learning has happened in agreed ways. Universities exist to award degrees, to the right people at the right time, and to do this responsibly they have to invest in the most robust administrative processes: enrolment management at one end, and lock tight records management at the other. Actual student learning is something they outsource to their academic faculty, who still achieve this with minimal management oversight except through feedback surveys.

But as we move towards a more competitive system, with tighter budgets and higher expectations for quality, we should probably notice that the LMS is also a performance monitoring system for teaching. Minimally this is being introduced through the development of institutional threshold standards for online learning practice, while the attention of analytics tools is technically towards the evidence of student engagement with learning. As more routine teaching shifts online, there is nothing whatsoever to inhibit the development of LMS analytics for staff performance evaluation—including of casual and sessional staff.

This is why even academics who find the LMS a pretty hopeless teaching environment need to keep an eye on its strategic development, and especially to pay close attention when institutions engage in the process of selecting a new LMS. Because behind all the blither about the transformation of the student learning experience, an enterprise level management system is exactly what it says on the tin.

* LMS week: it’s like Shark Week, only longer.